-

EPUB 233 KB

-

Kindle 297 KB

-

Support epubBooks by making a small $2.99 PayPal donation purchase.

This work is available in the U.S. and for countries where copyright is Life+70 or less.

Description

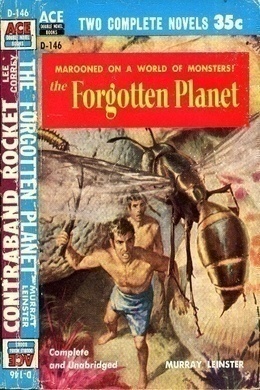

Beneath dense gray clouds through which no sun shone lay a forgotten planet. It was a nightmare world of grotesque and terrifying animal-plant life. Gigantic beetles, spiders, bugs and ants filled the putrid, musty earth-ready to kill and devour anything in sight. There were men amidst this horror-men who cringed and ran from the ravening monsters and huddled in the mushroom forests at night. Burl was one of these creatures. But one day inspiration hit Burl. He would find a weapon-he would fight back. And with this idea the first step was taken in man’s most desperate flight for freedom in this most horrible of all worlds. But it was only a first step.

224 pages with a reading time of ~3.50 hours (56077 words), and first published in 1954. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks, 2014.

Community Reviews

-

This was excellent. The story is a great take on the abandoned colony idea. Typical of the author, it keeps you interested and engaged.

Dec 24

Excerpt

In all his lifetime of perhaps twenty years, it had never occurred to Burl to wonder what his grandfather had thought about his surroundings. The grandfather had come to an untimely end in a fashion which Burl remembered as a succession of screams coming more and more faintly to his ears, while he was being carried away at the topmost speed of which his mother was capable.

Burl had rarely or never thought of his grandfather since. Surely he had never wondered what his great-grandfather had thought, and most surely of all he never speculated upon what his many-times-removed great-grandfather had thought when his lifeboat landed from the Icarus. Burl had never heard of the Icarus. He had done very little thinking of any sort. When he did think, it was mostly agonized effort to contrive a way to escape some immediate and paralyzing danger. When horror did not press upon him, it was better not to think, because there wasn’t much but horror to think about.

At the moment, he was treading cautiously over a brownish carpet of fungus, creeping furtively toward the stream which he knew only by the generic name of “water.” It was the only water he knew. Towering far above his head, three man-heights high, great toadstools hid the gray sky from his sight. Clinging to the yard-thick stalks of the toadstools were still other fungi, parasites upon the growths that once had been parasites themselves.

Burl appeared a fairly representative specimen of the descendants of the long-forgotten Icarus crew. He wore a single garment twisted about his middle, made from the wing-fabric of a great moth which the members of his tribe had slain as it emerged from its cocoon. His skin was fair without a trace of sunburn. In all his lifetime he had never seen the sun, though he surely had seen the sky often enough. It was rarely hidden from him save by giant fungi, like those about him now, and sometimes by the gigantic cabbages which were nearly the only green growths he knew. To him normal landscape contained only fantastic pallid mosses, and misshapen fungus growths, and colossal moulds and yeasts.

He moved onward. Despite his caution, his shoulder once touched a cream-colored toadstool stalk, giving the whole fungus a tiny shock. Instantly a fine and impalpable powder fell upon him from the umbrella like top above. It was the season when the toadstools sent out their spores. He paused to brush them from his head and shoulders. They were, of course, deadly poison.

Burl knew such matters with an immediate and specific and detailed certainty. He knew practically nothing else. He was ignorant of the use of fire, of metals, and even of the uses of stone and wood. His language was a scanty group of a few hundred labial sounds, conveying no abstractions and few concrete ideas. He knew nothing of wood, because there was no wood in the territory furtively inhabited by his tribe. This was the lowlands. Trees did not thrive here. Not even grasses and tree-ferns could compete with mushrooms and toadstools and their kin. Here was a soil of rusts and yeasts. Here were toadstool forests and fungus jungles. They grew with feverish intensity beneath a cloud-hidden sky, while above them fluttered butterflies no less enlarged than they, moths as much magnified, and other creatures which could thrive on their corruption.

The only creatures on the planet which crawled or ran or flew–save only Burl’s fugitive kind–were insects. They had been here before men came, and they had adapted to the planet’s extraordinary ways. With a world made ready before their first progenitors arrived, insects had thriven incredibly. With unlimited food-supplies, they had grown large. With increased size had come increased opportunity for survival, and enlargement became hereditary. Other than fungoid growths, the solitary vegetables were the sports of unstable varieties of the plants left behind by the Ludred. There were enormous cabbages, with leaves the size of ship-sails, on which stolid grubs and caterpillars ate themselves to maturity, and then swung below in strong cocoons to sleep the sleep of metamorphosis. The tiniest butterflies of Earth had increased their size here until their wings spread feet across, and some–like the emperor moths–stretched out purple wings which were yards in span. Burl himself would have been dwarfed beneath a great moth’s wing.

But he wore a gaudy fabric made of one. The moths and giant butterflies were harmless to men. Burl’s fellow tribesmen sometimes came upon a cocoon when it was just about to open, and if they dared they waited timorously beside it until the creature inside broke through its sleeping-shell and came out into the light.