-

EPUB 290 KB

-

Kindle 329 KB

-

Support epubBooks by making a small $2.99 PayPal donation purchase.

Description

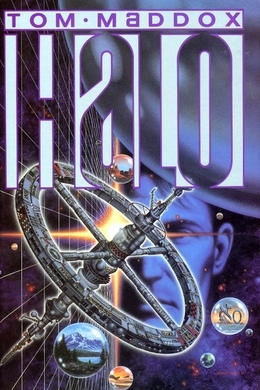

Something strange is happening on the high-orbital space station called Halo, and the men who run the corporation who own Halo don’t know what it is. SenTrax has hired freelance data auditor Mikhail Gonzales to find out. Why are the resources of Aleph, the artificial intelligence that operates Halo’s systems, being diverted to the experimental sections? Who authorized the extraordinary life-support systems being built? For more information visit the Tom Maddox website.

213 pages with a reading time of ~3.25 hours (53391 words), and first published in 1992. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks, 2015.

Community Reviews

There are currently no other reviews for this book.

Excerpt

On a rainy morning in Seattle, Gonzales was ready for the egg. A week ago he had returned from Myanmar, the country once known as Burma, and now, after two days of drugs and fasting, he was prepared: he had become an alien, at home in a distant landscape. His brain was filled with blossoms of fire, their spread white flesh torched to yellow, the center of a burning world. On the dark stained oak door, angel wings danced in blue flame, their faces beatific in the cold fire. Staring at the animated carved figures, Gonzales thought, the fire is in my eyes, in my brain. He pushed down the s-curved brass handle and stepped through to the hallway, his split-toed shoes of soft cotton and rope scuffing without noise across floors of bleached oak. Through the open door at the hallway’s end, morning’s light through stained glass made abstract patterns of crimson and buttery yellow. Inside the room, a blue monitor console stood against the far wall, SenTrax corporate sunburst glowing on its face; in the center of the room was the egg, split hemispheres of chromed steel, cracked and waiting. One half-egg was filled with beige tubes and snakes of optic cable, the other half with hard dark plastic lying slack against the shell. Gonzales rubbed his hands across his eyes, then pulled his hair back into a long hank and slipped a circle of elastic over it. He reached to his waist and grabbed the bottom hem of his navy blue t-shirt and pulled the shirt over his head. Dropping it to the floor, he kicked off his shoes, stepped out of baggy tan pants and loose white cotton underpants and stood naked, his pale skin gleaming with a light coat of sweat. His skin felt hot, eyes grainy, stomach sore. He stepped up and into a chrome half-egg, then shivered and lay back as body-warmth liquid bled into the slack plastic, which began to balloon underneath him. He took hold of finger-thick cables and pushed their junction ends home into the sockets set in the back of his neck. As the egg continued to fill, he fit a mask over his face, felt its edges seal, and inhaled. Catheters moved toward his crotch, iv needles toward the crooks of both arms. The egg shut closed on him and liquid spilled into its interior. He floated in silence, waiting, breathing slowly and deeply as elation punched through the chaotic mix of emotions generated by drugs, meditation, and the egg. No matter that he was going to relive his own terror, this was what moved him: access to the many-worlds of human experience—travel through space, time, and probability all in one. Virtual realities were everywhere—virtual vacations, sex, superstardom, you name it—but compared to the egg, they were just high-res videogames or stage magic. VRs used a variety of tricks to simulate physical presence, but the sensorium could be fooled only to a certain degree, and when you inhabited a VR, you were conscious of it, so sustaining its illusion depended on willing suspension of disbelief. With the egg, however, you got total involvement through all sensory modalities—the worlds were so compelling that people waking from them often seemed lost in the waking world, as if it were a dream. A needle punched into a membrane set in one of the neural cables and injected a neuropeptide mix. Gonzales was transported. It was the final day of Gonzales’s three week stay in Pagan, the town in central Myanmar where the government had moved its records decades earlier, in the wake of ethnic rioting in Yangon. He sat with Grossback, the Division Head of SenTrax Myanmar, at a central rosewood table in the main conference room. The table’s work stations, embedded oblongs of glass, lay dark and silent in front of them. Gonzales had come to Myanmar to do an information audit. The local SenTrax group supplied the Federated State of Myanmar with its primary information utilities: all its records of personnel and materiel, and all transactions among them. A month earlier, SenTrax Myanmar’s reports had triggered “look-see” alarms in the home company’s passive auditing programs, and Gonzales and his memex had been sent to look more closely at the raw data. So for twenty straight days Gonzales and the memex had explored data structures and their contents, testing nominal functional relationships against reality. Wherever there were movements of information, money, equipment or personnel, there were records, and the two followed. They searched cash trails, matched purchase orders to services and materiel, verified voucher signatures with personnel records, cross-checked the personnel records themselves against government databases, and traced the backgrounds and movements of the people they represented; they read contracts and back-chased to their bid and acquisition; they verified daily transaction logs.