-

EPUB 196 KB

-

Kindle 229 KB

-

Support epubBooks by making a small $2.99 PayPal donation purchase.

This work is available in the U.S. and for countries where copyright is Life+70 or less.

Description

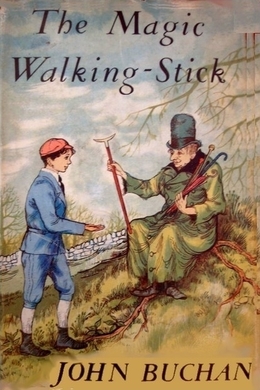

The Magic Walking Stick is a children’s short story by John Buchan. It tells the story of a teenage boy who buys a walking stick from a beggar - a magic walking stick that allows the boy to visit many places at his command…

151 pages with a reading time of ~2.50 hours (37991 words), and first published in 1932. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks, 2015.

Community Reviews

There are currently no other reviews for this book.

Excerpt

When Bill came back for long-leave that autumn half, he had before him a complicated programme of entertainment. Thomas, the keeper, whom he revered more than anyone else in the world, was to take him in the afternoon to try for a duck in the big marsh called Alemoor. In the evening Hallowe’en was to be celebrated in the nursery with his small brother Peter, and he was to be permitted to come down to dinner, and to sit up afterwards until ten o’clock. Next day, which was Sunday, would be devoted to wandering about with Peter, hearing from him all the appetising home news, and pouring into his greedy ears the gossip of the foreign world of school. On Monday morning, after a walk with the dogs, he was to motor to London, lunch with Aunt Alice, and then, after a noble tea, return to school in time for lock-up. This seemed to Bill to be all that could be desired in the way of excitement. But he did not know just how exciting that long-leave was destined to be. The first shadow of a cloud appeared after luncheon, when he had changed into knickerbockers and Thomas and the dogs were waiting by the gun-room door. Bill could not find his own proper stick. It was a long hazel staff, given him by the second stalker at Glenmore the year before—a staff rather taller than Bill, a glossy hazel, with a shapely polished crook, and without a ferrule, like all good stalking-sticks. He hunted for it high and low, but it could not be found. Without it in his hand Bill felt that the expedition lacked something vital, and he was not prepared to take instead one of his father’s shooting-sticks, as Groves, the butler, recommended. Nor would he accept a knobbly cane proffered by Peter. Feeling a little aggrieved and imperfectly equipped, he rushed out to join Thomas. He would cut himself an ashplant in the first hedge. In the first half-mile he met two magpies, and this should have told him that something was going to happen. It is right to take off your cap to a single magpie, or to three, or to five, but never to an even number, for an even number means mischief. But Bill, looking out for ashplants, was heedless, and had uncovered his head before he remembered the rule. Then, as he and Thomas ambled down the lane which led to Alemoor, they came upon an old man sitting under a hornbeam. This was the second warning, for of course a hornbeam is a mysterious tree. Moreover, though there were hornbeams in Bill’s garden, they did not flourish elsewhere in that countryside. Had Bill been on his guard he would have realised that the hornbeam had no business there, and that he had never seen it before. But there it was, growing in a grassy patch by the side of the lane, and under it sat an old man. He was a funny little wizened old man, in a shabby long green overcoat which had once been black; and he wore on his head the oldest and tallest and greenest bowler hat that ever graced a human head. It was quite as tall as the topper which Bill wore at school. Thomas, who had a sharp eye for poachers and vagabonds, did not stop to question him, but walked on as if he did not see him—which should have warned Bill that something queer was afoot. Also Gyp, the spaniel, and Shawn, the Irish setter, at the sight of him dropped their tails between their legs and remembered an engagement a long way off. But Bill stopped, for he saw that the old man had a bundle under his arm, a bundle of ancient umbrellas and odd, ragged sticks. The old man smiled at him, and he had eyes as bright and sharp as a bird’s. He seemed to know what was wanted, for he at once took a stick from his bundle. You would not have said that it was the kind of stick that Bill was looking for. It was short and heavy, and made of some dark foreign wood; and instead of a crook it had a handle shaped like a crescent, cut out of a white substance which was neither bone nor ivory. Yet Bill, as soon as he saw it, felt that it was the one stick in the world for him. “How much?” he asked. “One farthing,” said the old man, and his voice squeaked like a winter wind in a chimney. Now a farthing is not a common coin, but Bill happened to have one—a gift from Peter on his arrival that day, along with a brass cannon, five empty cartridges, a broken microscope, and a badly-printed, brightly-illustrated narrative called Two Villains Foiled. Peter was a famous giver. A farthing sounded too little, so Bill proffered one of his scanty shillings. “I said one farthing,” said the old man rather snappishly. The coin changed hands, and the little old man’s wizened face seemed to light up with an elfin glee. “‘Tis a fine stick, young sir,” he squeaked; “a noble stick, when you gets used to the ways of it.” Bill had to run to catch up Thomas, who was plodding along with the dogs, now returned from their engagement. “That’s a queer chap—the old stick-man, I mean,” he said.