-

EPUB 321 KB

-

Kindle 366 KB

-

Support epubBooks by making a small $2.99 PayPal donation purchase.

This work is available for countries where copyright is Life+70 or less.

Description

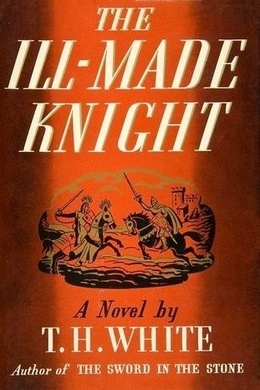

Lancelot, despite being the bravest of the knights, is ugly, and ape-like, so that he calls himself the Chevalier mal fet - “The Ill-Made Knight”. As a child, Lancelot loved King Arthur and spent his entire childhood training to be a knight of the round table. When he arrives and becomes one of Arthur’s knights, he also becomes the king’s close friend. This causes some tension, as he is jealous of Arthur’s new wife Guinevere. In order to please her husband, Guinevere tries to befriend Lancelot and the two eventually fall in love. T.H. White’s version of the tale elaborates greatly on the passionate love of Lancelot and Guinevere. Suspense is provided by the tension between Lancelot’s friendship for King Arthur and his love for and affair with the queen. The third book from the collection The Once and Future King.

310 pages with a reading time of ~4.75 hours (77504 words), and first published in 1940. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks, 2015.

Community Reviews

There are currently no other reviews for this book.

Excerpt

In the castle of Benwick, the French boy was looking at his face in the polished surface of a kettle-hat. It flashed in the sunlight with the stubborn gleam of metal. It was practically the same as the steel helmet which soldiers still wear, and it did not make a good mirror, but it was the best he could get. He turned the hat in various directions, hoping to get an average idea of his face from the different distortions which the bulges made. He was trying to find out what he was, and he was afraid of what he would find. The boy thought that there was something wrong with him. All through his life–even when he was a great man with the world at his feet–he was to feel this gap: something at the bottom of his heart of which he was aware, and ashamed, but which he did not understand. There is no need for us to try to understand it. We do not have to dabble in a place which he preferred to keep secret. The Armoury, where the boy stood, was lined with weapons of war. For the last two hours he had been whirling a pair of dumbbells in the air–he called them “poises”–and singing to himself a song with no words and no tune. He was fifteen. He had just come back from England, where his father King Ban of Benwick had been helping the English King to quell a rebellion. You remember that Arthur wanted to catch his knights young, to train them for the Round Table, and that he had noticed Lancelot at the feast, because he was winning most of the games. Lancelot, swinging his dumb-bells fiercely and making his wordless noise, had been thinking of King Arthur with all his might. He was in love with him. That was why he had been swinging the poises. He had been remembering all the words of the only conversation which he had held with his hero. The King had called him over when they were embarking for France–after he had kissed King Ban good-bye–and they had gone alone into a corner of the ship. The heraldic sails of Ban’s fleet, and the sailors in the rigging, and the armed turrets and archers and seagulls, like flake-white, had been a background to their conversation. “Lance,” the King had said, “come here a moment, will you?” “Sir.” “I was watching you playing games at the feast.” “Sir.” “You seemed to win most of them.” Lancelot squinted down his nose. “I want to get hold of a lot of people who are good at games, to help with an idea I have. It is for the time when I am a real King, and have got this kingdom settled. I was wondering whether you would care to help, when you are old enough?” The boy had made a sort of wriggle, and had suddenly flashed his eyes at the speaker. “It is about knights,” Arthur had continued. “I want to have an Order of Chivalry, like the Order of the Garter, which goes about fighting against Might. Would you like to be one of those?” “Yes.” The King had looked at him closely, unable to see whether he was pleased or frightened or merely being polite. “Do you understand what I am talking about?” Lancelot had taken the wind out of his sails. “We call it Fort Mayne in France,” he had explained. “The man with the strongest arm in a clan gets made the head of it, and does what he pleases. That is why we call it Fort Mayne. You want to put an end to the Strong Arm, by having a band of knights who believe in justice rather than strength. Yes, I would like to be one of those very much. I must grow up first. Thank you. Now I must say good-bye.” So they had sailed away from England–the boy standing in the front of the ship and refusing to look back, because he did not want to show his feelings. He had already fallen in love with Arthur on the night of the wedding feast, and he carried with him in his heart to France the picture of that bright northern king, at supper, flushed and glorious from his wars. Behind the black eyes which were searching intently in the kettle-hat there was a dream which had come to him the previous night. Seven hundred years ago–or it may have been fifteen hundred according to Malory’s notation–people took dreams as seriously as the psychiatrists do today, and Lancelot’s had been a disturbing one. It was not disturbing because of anything it might mean–for he had not the least idea of its meaning–but because it had left him with a sense of loss. This was what it was.