-

EPUB 307 KB

-

Kindle 374 KB

-

Support epubBooks by making a small $2.99 PayPal donation purchase.

This work is available for countries where copyright is Life+70 or less.

Description

During the morning Captain Crowther stood beside his helmsman at the high wheel on the roof of the steamer. The Second Defile with its monstrous, high cliff, its racing waters, and the unmanageable great rafts of teak wood floating down to Rangoon presented always a delicate problem in navigation. But Captain Crowther certainly knew his business. He edged his steamer in here, thrust a raft aside there, and by lunch-time the hills had fallen back and we were thrashing down the broader waterway to Schwegu. At luncheon Crowther took the head of the table and I found that a place had been laid for me at his elbow. He was a man of thirty-six years or so, and he had the sort of hard, leering, and wicked face the early craftsmen were so fond of carving on the groins and pillars of French cathedrals. I took a dislike to him at my first glance.

317 pages with a reading time of ~5 hours (79402 words), and first published in 1933. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks, 2017.

Community Reviews

There are currently no other reviews for this book.

Excerpt

I cannot pretend that the world is waiting for this story, for the world knows nothing about it. But I want to tell it. No one knows it better than I do, except Michael Crowther, and he, nowadays, has time for nothing but his soul.

And for only the future of that. He is not concerned with its past history. The days of his unregenerate activities lie hidden in a cloud behind his back. He watches another cloud in front of him lit with the silver–I can’t call it the gold–of the most extraordinary hope which ever warmed a myriad of human beings. But it is in that past history of his soul and in those activities that the heart of this story lies. I was at once near enough to the man and far enough away from him to accept and understand his startling metamorphoses. I took my part in that dangerous game of Hunt the Slipper which was played across half the earth. Dangerous, because the slipper was a precious stone set in those circumstances of crime and death which attend upon so many jewels. I saw the affair grow from its trumpery beginnings until, like some mighty comet, it swept into its blaze everyone whom it approached. It roared across the skies carrying us all with it, bringing happiness to some and disaster to others. I am Christian enough to believe that there was a pattern and an order in its course; though Michael Crowther thought such a doctrine to be mystical and a sin. Finally, after these fine words, I was at the core of these events from the beginning. Indeed I felt the wind of them before it blew.

Thus:

My father held a high position in the Forest Company and I was learning the business from the bottom so that when the time came I might take his place. I had been for the last six months travelling with the overseer whose province it was to girdle those teak trees which were ripe for felling. The life was lonely, but to a youth of twenty-two the most enviable in the world. There was the perpetual wonder of the forest; the changes of light upon branch and leaf which told the hours like the hands of a clock; the fascination to a novice of the rudiments of tree-knowledge, the silence and the space; and some very good shooting besides. Apart from game for the pot, I had got one big white tiger ten feet long as he lay, a t’sine, and a few sambur with excellent heads. I had the pleasant prospect, too, of returning to England for the months of the rainy season, and giving the girls there a treat they seldom got.

I parted from the overseer in order to make the Irrawaddy at Sawadi, a little station on the left bank of the river below Bhamo, but above the vast cliff which marks the entrance to the Second Defile. The distance was greater than a long day’s march, but one of the Company’s rest-houses was built conveniently a few miles from the station. I reached it with my small baggage train and my terrier, about seven o’clock of the evening. A small bungalow was raised upon piles with steps leading up to the door, and a hut with the kitchen and a sleeping-place for the servants was built close by. Both the buildings were set in a small clearing. I ate my dinner, smoked a cheroot, put myself into my camp bed and slept as tired twenty-two should sleep, with the immobility of the dead.

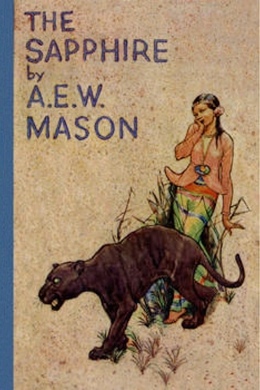

But towards morning some instinct alert in a subconscious cell began to ring its tiny bells and telegraph a warning to my nerve centres that it would be wise to wake up. I resisted, but the bells were ringing too loudly–and suddenly I was awake. I was lying upon my left side with my face towards the open door, and fortunately I had not moved when I awaked. The moon rode high and the clearing to the edge of the trees lay in a blaze of silver light. Against that clear bright background at the top of the steps, on the very threshold of the door, a huge black panther sat up like a cat. His tail switched slowly from side to side and his eyes stared savagely into the dark room. They were like huge emeralds, except that no emerald ever held such fire.

“He wants my terrier dog, Dick,” I explained to myself. I could hear the poor beast shivering under the bed. “But that won’t help me if he crouches and springs.”

My rifle lay on a table across the room. To jump out of bed and make a dash for it was merely to precipitate the brute’s attack. Moreover, even were I to reach it, it was unloaded. So I lay still except for my heart; and the panther sat still except for his tail. He was working out his tactics; I was hoping that I was not shivering quite so cravenly as my unhappy little terrier dog beneath my bed. As I watched, to my utter horror the panther began to crouch, very slowly, pushing back his haunches, settling himself down upon them for a spring. And that spring would land him surely on the top of the bed and me.

I found myself saying silently to myself, and stupidly: