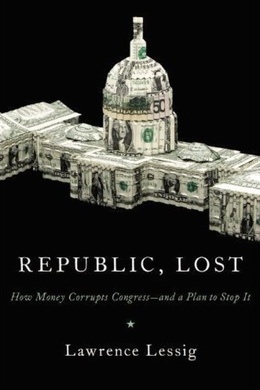

Republic, Lost (v1.0)

How Money Corrupts Congress--and a Plan to Stop It

by Lawrence Lessig

subjects: Politics & Government, Political Economy

-

EPUB 756 KB

-

Kindle 947 KB

-

Support epubBooks by making a small $2.99 PayPal donation purchase.

Description

In an era when special interests funnel huge amounts of money into our government-driven by shifts in campaign-finance rules and brought to new levels by the Supreme Court in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission-trust in our government has reached an all-time low. More than ever before, Americans believe that money buys results in Congress, and that business interests wield control over our legislature. With heartfelt urgency and a keen desire for righting wrongs, Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig takes a clear-eyed look at how we arrived at this crisis: how fundamentally good people, with good intentions, have allowed our democracy to be co-opted by outside interests, and how this exploitation has become entrenched in the system. Rejecting simple labels and reductive logic-and instead using examples that resonate as powerfully on the Right as on the Left-Lessig seeks out the root causes of our situation. He plumbs the issues of campaign financing and corporate lobbying, revealing the human faces and follies that have allowed corruption to take such a foothold in our system. He puts the issues in terms that nonwonks can understand, using real-world analogies and real human stories. And ultimately he calls for widespread mobilization and a new Constitutional Convention, presenting achievable solutions for regaining control of our corrupted-but redeemable-representational system. In this way, Lessig plots a roadmap for returning our republic to its intended greatness. While America may be divided, Lessig vividly champions the idea that we can succeed if we accept that corruption is our common enemy and that we must find a way to fight against it. He not only makes this need palpable and clear, but he gives us the practical and intellectual tools to do something about it. Lessig released a “revised and expanded [edition] in time for the 2016 election”. Purchase a copy from the official Republic v2 site.

401 pages with a reading time of ~6.25 hours (100278 words), and first published in 2011. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks, 2017.

Community Reviews

There are currently no other reviews for this book.

Excerpt

Good Souls, Corrupted In the summer of 1991, I spent a month alone on a beach in Costa Rica reading novels. I had just finished clerking at the Supreme Court. That experience had depressed me beyond measure. I had idolized the Court. It turns out humans work there. It would take me years to relearn just how amazing that institution actually is. Before that, I was to begin teaching at the University of Chicago Law School. I needed to clear my head. I was staying at a small hotel near Jaco. In the center of the hotel was a large open-air restaurant. At one end hung a TV, running all the time. The programs were in Spanish and hence incomprehensible to me. The one bit someone did translate was a warning that flashed before the station aired The Simpsons, advising parents that the show was “antisocial,” not appropriate for kids. Midway through that month, however, that television became the center of my life. On Monday, August 19, I watched with astonishment the coverage of Russia’s August Putsch, when hard-line Communists tried to wrest control of the nation from the reformer Mikhail Gorbachev. Tanks were in the streets. Two years after Tiananmen, it felt inevitable that something dramatic, and tragic, was going to happen. Again. I sat staring at the TV for most of the day. I pestered people to interpret the commentary for me. I annoyed the bartender by not drinking as I consumed the free TV. And I watched with geeky awe as Boris Yeltsin climbed on top of a tank and challenged his nation to hold on to the democracy the old Communists were trying to steal. I will always remember that image. As with waking up to the Challenger disaster or watching the reports of Bobby Kennedy’s assassination, I can remember those first moments almost as clearly as if they were happening now. And I vividly remember thinking about the extraordinary figure that Yeltsin was: bravely challenging in the name of freedom a coup that if successful—and on August 19 there was no reason to doubt it would be—would certainly result in the execution of this increasingly idolized defender of the people. Every other player in that mix seemed tainted or compromised, Gorbachev especially. And compromise (what life at the Court had shown me) was exactly what the month away was to allow me to escape. So at that moment, Yeltsin was the focus for me. Here was a man who could be for Russia what George Washington had been for America. History had given him the opportunity to join its exclusive club. It had taken some initial courage for him to climb on, but on August 19, 1991, I couldn’t imagine how he could do anything other than ride this opportunity to its inevitable end. If democracy seemed possible for the former Soviets, it seemed possible only because it would have a voice through the rough and angry Yeltsin. That’s not, of course, how the story played out. No doubt Yeltsin’s position was impossibly difficult. But over the balance of the 1990s, the heroic Yeltsin became a joke. Perhaps unfairly—and certainly unfairly at the beginning, since his real troubles with alcohol began only after he became Russia’s president.—he was increasingly viewed as a drunk. After his first summit with Yeltsin, Clinton became convinced that his addiction was “more than a sporting problem.” The public didn’t even learn about the most incredible incident until two years ago: on a visit to Washington to meet with Clinton, Yeltsin was found by the Secret Service on a D.C. street in the predawn hours, dressed only in underwear, trying in vain to flag down a taxi to take him to get pizza. Yeltsin fumbled his chance at history, all because of the lure of the bottle. As clearly as I remember watching him on that tank on August 19, I remember thinking, over the balance of that decade, about the special kind of bathos that Yeltsin betrayed. He was handed a chance to save Russia from authoritarians. Yet even this gift wasn’t enough to inspire him to stay straight. Yeltsin is a type: a particular, and tragic, character type. No doubt a good soul, he wanted and worked to do good for his nation. But he failed, in part because of a dependency that conflicted with his duty to his nation. We can’t hate him. We could possibly feel sorry for him. And we should certainly feel sorry for the millions who lost the chance of a certain kind of free society because of this man’s dependency.