-

EPUB 264 KB

-

Kindle 308 KB

-

Support epubBooks by making a small $2.99 PayPal donation purchase.

Description

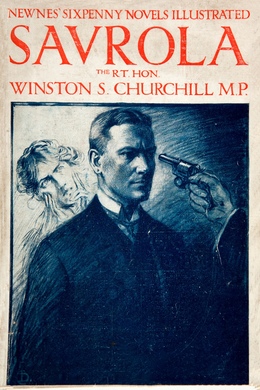

A fast-paced thriller written near the end of Queen Victoria’s reign when Great Britain ruled a worldwide empire, it subtly reveals the political awareness and personal views of a young Churchill, decades before he would become one of the most important figures of the twentieth century. Savrola shows that it is possible to obtain penetrating insights into an author’s mind from their fiction as well as from their biography. The story concerns the events leading up to, during and after a revolution in the fictional European country of Laurania.

228 pages with a reading time of ~3.50 hours (57224 words), and first published in 1900. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks, 2017.

Community Reviews

There are currently no other reviews for this book.

Excerpt

There had been a heavy shower of rain, but the sun was already shining through the breaks in the clouds and throwing swiftly changing shadows on the streets, the houses, and the gardens of the city of Laurania. Everything shone wetly in the sunlight: the dust had been laid; the air was cool; the trees looked green and grateful. It was the first rain after the summer heats, and it marked the beginning of that delightful autumn climate which has made the Lauranian capital the home of the artist, the invalid, and the sybarite.

The shower had been heavy, but it had not dispersed the crowds that were gathered in the great square in front of the Parliament House. It was welcome, but it had not altered their anxious and angry looks; it had drenched them without cooling their excitement. Evidently an event of consequence was taking place. The fine building, where the representatives of the people were wont to meet, wore an aspect of sombre importance that the trophies and statues, with which an ancient and an art-loving people had decorated its façade, did not dispel. A squadron of Lancers of the Republican Guard was drawn up at the foot of the great steps, and a considerable body of infantry kept a broad space clear in front of the entrance. Behind the soldiers the people filled in the rest of the picture. They swarmed in the square and the streets leading to it; they had scrambled on to the numerous monuments, which the taste and pride of the Republic had raised to the memory of her ancient heroes, covering them so completely that they looked like mounds of human beings; even the trees contained their occupants, while the windows and often the roofs, of the houses and offices which overlooked the scene were crowded with spectators. It was a great multitude and it vibrated with excitement. Wild passions surged across the throng, as squalls sweep across a stormy sea. Here and there a man, mounting above his fellows, would harangue those whom his voice could reach, and a cheer or a shout was caught up by thousands who had never heard the words but were searching for something to give expression to their feelings.

It was a great day in the history of Laurania. For five long years since the Civil War the people had endured the insult of autocratic rule. The fact that the Government was strong, and the memory of the disorders of the past, had operated powerfully on the minds of the more sober citizens. But from the first there had been murmurs. There were many who had borne arms on the losing side in the long struggle that had ended in the victory of President Antonio Molara. Some had suffered wounds or confiscation; others had undergone imprisonment; many had lost friends and relations, who with their latest breath had enjoined the uncompromising prosecution of the war. The Government had started with implacable enemies, and their rule had been harsh and tyrannical. The ancient constitution to which the citizens were so strongly attached and of which they were so proud, had been subverted. The President, alleging the prevalence of sedition, had declined to invite the people to send their representatives to that chamber which had for many centuries been regarded as the surest bulwark of popular liberties. Thus the discontents increased day by day and year by year: the National party, which had at first consisted only of a few survivors of the beaten side, had swelled into the most numerous and powerful faction in the State; and at last they had found a leader. The agitation proceeded on all sides. The large and turbulent population of the capital were thoroughly devoted to the rising cause. Demonstration had followed demonstration; riot had succeeded riot; even the army showed signs of unrest. At length the President had decided to make concessions. It was announced that on the first of September the electoral writs should be issued and the people should be accorded an opportunity of expressing their wishes and opinions.

This pledge had contented the more peaceable citizens. The extremists, finding themselves in a minority, had altered their tone. The Government, taking advantage of the favourable moment, had arrested several of the more violent leaders. Others, who had fought in the war and had returned from exile to take part in the revolt, fled for their lives across the border. A rigorous search for arms had resulted in important captures. European nations, watching with interested and anxious eyes the political barometer, were convinced that the Government cause was in the ascendant. But meanwhile the people waited, silent and expectant, for the fulfilment of the promise.