-

EPUB 301 KB

-

Kindle 363 KB

-

Support epubBooks by making a small $2.99 PayPal donation purchase.

This work is available for countries where copyright is Life+70 or less.

Description

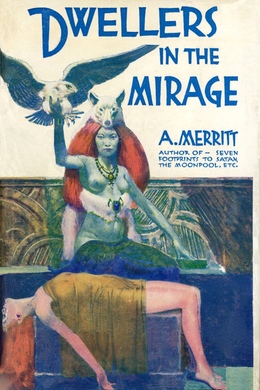

Angry Warrior, Modern Man… Leif Langdon was suddenly ripped from the 20th century and plunged into the ancient world of The Mirage. But his entrance into this awesome land awakened the slumbering Dwayanu, who in this strange incarnation was also Leif. Thus, two-men-in-one battle with the beautiful witch-woman Lur and the ethereal beauty Evalie for the glory of The Mirage.

307 pages with a reading time of ~4.75 hours (76754 words), and first published in 1932. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks, 2017.

Community Reviews

There are currently no other reviews for this book.

Excerpt

I raised my head, listening,–not only with my ears but with every square inch of my skin, waiting for recurrence of the sound that had awakened me. There was silence, utter silence. No soughing in the boughs of the spruces clustered around the little camp. No stirring of furtive life in the underbrush. Through the spires of the spruces the stars shone wanly in the short sunset to sunrise twilight of the early Alaskan summer.

A sudden wind bent the spruce tops, carrying again the sound–the clangour of a beaten anvil.

I slipped out of my blanket, and round the dim embers of the fire toward Jim. His voice halted me.

“All right, Leif. I hear it.”

The wind sighed and died, and with it died the humming aftertones of the anvil stroke. Before we could speak, the wind arose. It bore the after-hum of the anvil stroke–faint and far away. And again the wind died, and with it the sound.

“An anvil, Leif!”

“Listen!”

A stronger gust swayed the spruces. It carried a distant chanting; voices of many women and men singing a strange, minor theme. The chant ended on a wailing chord, archaic, dissonant.

There was a long roll of drums, rising in a swift crescendo, ending abruptly. After it a thin and clamorous confusion.

It was smothered by a low, sustained rumbling, like thunder, muted by miles. In it defiance, challenge.

We waited, listening. The spruces were motionless. The wind did not return.

“Queer sort of sounds, Jim.” I tried to speak casually. He sat up. A stick flared up in the dying fire. Its light etched his face against the darkness–thin, and brown and hawk-profiled. He did not look at me.

“Every feathered forefather for the last twenty centuries is awake and shouting! Better call me Tsantawu, Leif. Tsi’ Tsa’lagi–I am a Cherokee! Right now–all Indian.”

He smiled, but still he did not look at me, and I was glad of that.

“It was an anvil,” I said. “A hell of a big anvil. And hundreds of people singing…and how could that be in this wilderness…they didn’t sound like Indians…”

“The drums weren’t Indian.” He squatted by the fire, staring into it. “When they turned loose, something played a pizzicato with icicles up and down my back.”

“They got me, too–those drums!” I thought my voice was steady, but he looked up at me sharply; and now it was I who averted my eyes and stared at the embers. “They reminded me of something I heard…and thought I saw…in Mongolia. So did the singing. Damn it, Jim, why do you look at me like that?”

I threw a stick on the fire. For the life of me I couldn’t help searching the shadows as the stick flamed. Then I met his gaze squarely.

“Pretty bad place, was it, Leif?” he asked, quietly. I said nothing. Jim got up and walked over to the packs. He came back with some water and threw it over the fire. He kicked earth on the hissing coals. If he saw me wince as the shadows rushed in upon us, he did not show it.

“That wind came from the north,” he said. “So that’s the way the sounds came. Therefore, whatever made the sounds is north of us. That being so–which way do we travel to-morrow?”

“North,” I said.

My throat dried as I said it.

Jim laughed. He dropped upon his blanket, and rolled it around him. I propped myself against the bole of one of the spruces, and sat staring toward the north.

“The ancestors are vociferous, Leif. Promising a lodge of sorrow, I gather–if we go north…’Bad Medicine!’ say the ancestors… ‘Bad Medicine for you, Tsantawu! You go to Usunhi’yi, the Darkening-land, Tsantawu!…Into Tsusgina’i, the ghost country! Beware! Turn from the north, Tsantawu!‘”

“Oh, go to sleep, you hag-ridden redskin!”

“All right, I’m just telling you.”

Then a little later:

”‘And heard ancestral voices prophesying war’–it’s worse than war these ancestors of mine are prophesying, Leif.”

“Damn it, will you shut up!”

A chuckle from the darkness; thereafter silence.

I leaned against the tree trunk. The sounds, or rather the evil memory they had evoked, had shaken me more than I was willing to admit, even to myself. The thing I had carried for two years in the buckskin bag at the end of the chain around my neck had seemed to stir; turn cold. I wondered how much Jim had divined of what I had tried to cover…

Why had he put out the fire? Because he had known I was afraid? To force me to face my fear and conquer it?…Or had it been the Indian instinct to seek cover in darkness?…By his own admission, chant and drum-roll had played on his nerves as they had on mine…

Afraid! Of course it had been fear that had wet the palms of my hands, and had tightened my throat so my heart had beaten in my ears like drums.

Like drums…yes!