-

EPUB 288 KB

-

Kindle 315 KB

-

Support epubBooks by making a small $2.99 PayPal donation purchase.

This work is available for countries where copyright is Life+70 or less.

Description

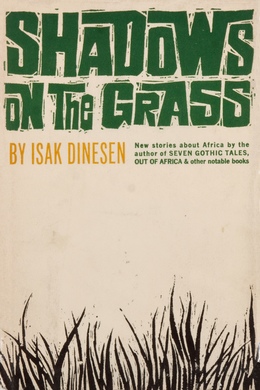

Blixen takes up the absorbing story of her life in Kenya begun in the unforgettable Out of Africa, which she published under the name of Isak Dinesen. With warmth and humanity these four stories illuminate her love both for the African people, their dignity and traditions, and for the beauty and wildness of the landscape. The first three were written in the 1950s and the last, ‘Echoes from the Hills’, was written especially for this volume in the summer of 1960 when the author was in her seventies. In all they provide a moving final chapter to her African reminiscences.

118 pages with a reading time of ~2 hours (29677 words), and first published in 1961. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks, 2018.

Community Reviews

There are currently no other reviews for this book.

Excerpt

As here, after twenty-five years, I again take up episodes of my life in Africa, one figure, straight, candid, and very fine to look at, stands as doorkeeper to all of them: my Somali servant Farah Aden. Were any reader to object that I might choose a character of greater importance, I should answer him that that would not be possible.

Farah came to meet me in Aden in 1913, before the First World War. For almost eighteen years he ran my house, my stables and safaris. I talked to him about my worries as about my successes, and he knew of all that I did or thought. Farah, by the time I had had to give up the farm and was leaving Africa, saw me off in Mombasa. And as I watched his dark immovable figure on the quay growing smaller and at last disappear, I felt it as if I were losing a part of myself, as if I were having my right hand set off, and from now on would never again ride a horse or shoot with a rifle, nor be able to write otherwise than with my left hand. Neither have I since then ridden or shot.

In order to form and make up a Unity, in particular a creative Unity, the individual components must needs be of different nature, they should even be in a sense contrasts. Two homogeneous units will never be capable of forming a whole, or their whole at its best will remain barren. Man and woman become one, a physically and spiritually creative Unity, by virtue of their dissimilarity. A hook and an eye are a Unity, a fastening; but with two hooks you can do nothing. A right-hand glove with its contrast the left-hand glove makes up a whole, a pair of gloves; but two right-hand gloves you throw away. A number of perfectly similar objects do not make up a whole–a couple of cigarettes may quite well be three or nine. A quartet is a Unity because it is made up of dissimilar instruments. An orchestra is a Unity, and may be perfect as such, but twenty double-basses striking up the same tune are Chaos.

A community of but one sex would be a blind world. When in 1940 I was in Berlin, engaged by three Scandinavian papers to write about Nazi Germany, woman–and the whole world of woman–was so emphatically subdued that I might indeed have been walking about in such a one-sexed community. I felt a relief then, as I watched the young soldiers marching west, to the frontier, for in a fight the adversaries become one, and the two duellists make up a Unity.

The introduction into my life of another race, essentially different from mine, in Africa became to me a mysterious expansion of my world. My own voice and song in life there had a second set to it, and grew fuller and richer in the duet.

Within the literature of the ages one particular Unity, made up of essentially different parts, makes its appearance, disappears and again comes back: that of Master and Servant. We have met the two in rhyme, blank verse and prose, and in the varying costumes of the centuries. Here wanders the Prophet Elisha with his servant Gehazi–between whom one would have supposed the partnership to have come to an end after the affair with Naaman, but whom we meet in a later chapter apparently in the best of understanding. Here walk Terence’s Davus and Simo, and Plautus’ Calidorus and Pseudolus. Here Don Quixote rides forth, with Sancho Panza on his mule by the croup of Rosinante. Here the Fool follows King Lear across the heath in the storm and the black night, here Leporello waits in the street while inside the palazzo Don Giovanni “reaps his sweet reward.” Phileas Fogg struts on to the stage with one single idea in his head and versatile Passepartout at his heels. In our own streets of old Copenhagen Jeronimus and Magdelone promenade arm in arm, while behind their broad and dignified backs Henrik and Pernille make signs to one another.

The servant may be the more fascinating of the two, still it holds true of him as of his master that his play of colours would fade and his timbre abate, were he to stand alone. He needs a master in order to be himself. Leporello, after having witnessed his scapegrace master’s lurid end, will still, I believe, from time to time in a circle of friends have produced his list of Don Giovanni’s victims and have read out triumphantly: “In Spain are a thousand and three!” The Fool, who is killed by the endless night on the moor, would not have become immortal without the mad old King, to whose lion’s roar he joins his doleful, bitter and tender mockery. Henrik and Pernille, if left by Holberg in their own native milieu of Copenhagen valets and ladies’ maids, would not have twinkled and sparkled as they do against the background of the sedateness of Jeronimus and Magdelone and the pale romance of Leander and Leonore.