-

EPUB 282 KB

-

Kindle 351 KB

-

Support epubBooks by making a small $2.99 PayPal donation purchase.

This work is available for countries where copyright is Life+70 or less.

Description

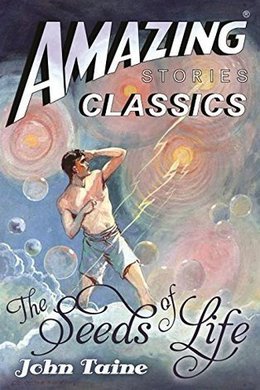

This is the story of Neils Bork, an alcoholic and failure raised to supernal heights of scientific genius and altruism by a scientific accident. And it is the story of what became of his golden dream of free, limitless energy for all, and of the marriage he thought would be crowned with glorious offspring.

This amazingly prophetic novel, which some say inspired Flowers for Algernon (on which the film Charlie was based), is easily the best novel Hugo Gernsback ever published in Amazing Stories. It features characters so mature their like would not be seen again until the post-war SF of the 1950s, and a theme that, in its rise and fall, prefigures that of Flowers for Algernon and carries it to a level of operatic tragedy not to be equaled until Bester’s The Demolished Man.

‘A superb tale that every lover of science fiction will want to have around. Completely off-trail science fiction—and highly recommended therefore.’ -Galaxy Science Fiction

276 pages with a reading time of ~4.25 hours (69085 words), and first published in 1931. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks, 2018.

Community Reviews

There are currently no other reviews for this book.

Excerpt

“DANGER. KEEP OUT.” This curt warning in scarlet on the bright green steel door of the twenty million volt electric laboratory was intended for the curious public, not for the intrepid researchers, should one of the latter carelessly forget to lock the door after him.

The laboratory itself, a severe box of reinforced concrete, might have been mistaken by the casual visitor as a modern factory but for the fact that it had no windows. This was no mere whim of the erratic architect; certain experiments must be carried out by their own light or in the dim glow of carefully filtered illumination from artificial sources. The absence of windows gave the massive rectangular block a singularly forbidding aspect. An imaginative artist might have said the laboratory had a sinister appearance, and only a scientist would have contradicted him. To the daring workers who tamed the man-made lightnings in it, the twenty million volt laboratory was more beautiful than the Parthenon in its prime.

Of the thousands who passed the laboratory daily on their way to or from work in the city of Seattle, perhaps a scant half dozen gave it so much as a passing glance. It was just another building, as barren of romance as a shoe factory. The charm of the Erickson Foundation for Electrical Research was not visible to a casual inspection. Nevertheless, its fascination was a vivid fact to the eighty men who slaved in its laboratories twelve or eighteen hours a day, regardless of all time clocks or other devices to coerce the unwilling to earn their wages. Their one trial was the fussy Director of the Foundation; work was a delight.

About three o’clock of a brilliant May afternoon, Andrew Crane and his technical assistant, the stocky Neils Bork, gingerly approached the forbidding door, carrying the last unit of Crane’s latest invention. This was a massive cylinder of Jena glass, six feet long by three in diameter, open at one end and sealed at the other by an enormous metal cathode like a giant’s helmet. It had cost the pair four months of unremitting labor and heart-breaking setbacks to perfect this evil-looking crown to Crane’s masterpiece. Therefore, they proceeded cautiously, firmly planting both feet on one granite step before venturing to fumble for the next.

Their final tussle in the workshops of the Foundation had endured nineteen hours. The job of sealing the cathode to the glass had to be done at one spurt, or not at all. During all that grueling grind neither man had dared to turn aside from the blowpipe for a second. In the nervous tension of succeeding at last, they had not felt the lack of food, water, or sleep. They had failed too often already, each time with the prize but a few hours ahead of them, to lose it again for a cup of water.

Crane planted his right foot firmly on the last, broad step. His left followed. He was up, his arms trembling from exhaustion. Bork cautiously felt for the top step. Then abused nature took her sardonic revenge for nineteen hours’ flouting of her rights. The groping foot failed to clear the granite by a quarter of an inch. In a fraction of a second, four months’ agonizing labor was as if it had never been.

Crane was a tall, lean Texan, of about twenty-seven, desiccated, with a long, cadaverous face and a constant dry grin about his mouth. He shunned unnecessary speech, except when a tube or valve suddenly burnt itself out owing to some oversight of his own. When Bork blundered, Crane as a rule held his tongue. But he grinned. Bork wished at such awkward moments that the lank Texan would at least swear. He never did; he merely smiled. Neils Bork was a true Nordic type, blue-eyed, yellow-haired, stockily built. From his physical appearance he should have been a steady, self-reliant technician. Unfortunately he was not as reliable as he might have been, had he given himself half a chance.

Viewing the shattered glass and the elaborate cathode, which had skipped merrily down the granite steps, and was now lying like a capsized turtle on its cracked back thirty feet away in the middle of the cement sidewalk, Crane grinned. Bork tried not to look at his companion’s face. He failed.

“I couldn’t help it,” he blurted out.

It was a foolish thing to have said. Of course he couldn’t ‘help it’–now. Only an imbecile would have deliberately smashed an intricate piece of apparatus that had taken months of sweating toil to perfect. Bork’s indiscretion loosened Crane’s reluctant tongue.

“You could help it,” he snapped, “if you’d let the booze alone. Look at me! I’m as steady as a rock. You’re shaking all over. Cut it out after this, or I’ll cut you out.”

“I haven’t touched a drop for–” the wretched Bork began in self-defense, but Crane cut him short.

“Twenty hours! I smelt your breath when you came to work yesterday morning. Of course you can’t control your legs when you’re half-stewed all the time.”