-

EPUB 526 KB

-

Kindle 652 KB

-

Support epubBooks by making a small $2.99 PayPal donation purchase.

This work is available for countries where copyright is Life+70 or less.

Description

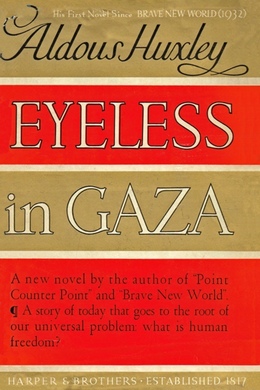

Anthony Beavis is a man inclined to recoil from life. His past is haunted by the death of his best friend Brian and by his entanglement with the cynical and manipulative Mary Amberley. Realising that his determined detachment from the world has been motivated not by intellectual honesty but by moral cowardice, Anthony attempts to find a new way to live. Eyeless in Gaza is considered by many to be Huxley’s definitive work of fiction.

586 pages with a reading time of ~9 hours (146726 words), and first published in 1936. This DRM-Free edition published by epubBooks, 2019.

Community Reviews

There are currently no other reviews for this book.

Excerpt

The snapshots had become almost as dim as memories. This young woman who had stood in a garden at the turn of the century was like a ghost at cockcrow. His mother, Anthony Beavis recognized. A year or two, perhaps only a month or two, before she died. But fashion, as he peered at the brown phantom, fashion is a topiary art. Those swan-like loins! That long slanting cascade of bosom—without any apparent relation to the naked body beneath! And all that hair, like an ornamental deformity on the skull! Oddly hideous and repellent it seemed in 1933. And yet, if he shut his eyes (as he could not resist doing), he could see his mother languidly beautiful on her chaise-longue; or, agile, playing tennis; or swooping like a bird across the ice of a far-off winter.

It was the same with these snapshots of Mary Amberley, taken ten years later. The skirt was as long as ever, and within her narrower bell of drapery woman still glided footless, as though on castors. The breasts, it was true, had been pushed up a bit, the redundant posterior pulled in. But the general shape of the clothed body was still strangely improbable. A crab shelled in whalebone. And this huge plumed hat of 1911 was simply a French funeral of the first class. How could any man in his senses have been attracted by so profoundly anti-aphrodisiac an appearance? And yet, in spite of the snapshots, he could remember her as the very embodiment of desirability. At the sight of that feathered crab on wheels his heart had beaten faster, his breathing had become oppressed.

Twenty years, thirty years after the event, the snapshots revealed only things remote and unfamiliar. But the unfamiliar (dismal automatism!) is always the absurd. What he remembered, on the contrary, was the emotion felt when the unfamiliar was still the familiar, when the absurd, being taken for granted, had nothing absurd about it. The dramas of memory are always Hamlet in modern dress.

How beautiful his mother had been—beautiful under the convoluted wens of hair and in spite of the jutting posterior, the long slant of bosom. And Mary, how maddeningly desirable even in a carapace, even beneath funereal plumes! And in his little fawn-coloured covert coat and scarlet tam-o’-shanter; as Bubbles, in grass-green velveteen and ruffles; at school in his Norfolk suit with the knickerbockers that ended below the knees in two tight tubes of box-cloth; in his starched collar and his bowler, if it were Sunday, his red-and-black school-cap on other days—he too, in his own memory, was always in modern dress, never the absurd little figure of fun these snapshots revealed. No worse off, so far as inner feeling was concerned, than the little boys of thirty years later in their jerseys and shorts. A proof, Anthony found himself reflecting impersonally, as he examined the top-hatted and tail-coated image of himself at Eton, a proof that progress can only be recorded, never experienced. He reached out for his note-book, opened it and wrote: ‘Progress may, perhaps, be perceived by historians; it can never be felt by those actually involved in the supposed advance. The young are born into the advancing circumstances, the old take them for granted within a few months or years. Advances aren’t felt as advances. There is no gratitude—only irritation if, for any reason, the newly invented conveniences break down. Men don’t spend their time thanking God for cars; they only curse when the carburettor is choked.’

He closed the book and returned to the top-hat of 1907.